Today’s modern sensors in high-end cameras offer a part of a powerful scanning solution. They have a high dynamic range needed to do justice to a Kodachrome’s density range and the resolution to image the fine details. Using the highest resolution sensors you can meet many of today’s applications, but the camera has to be matched with an appropriate lens, and the lighting is critical too.

A future article will talk about marrying the correct lens, light, and film transport, to the sensor so you can achieve the needed density range and detail for many film scanning applications.

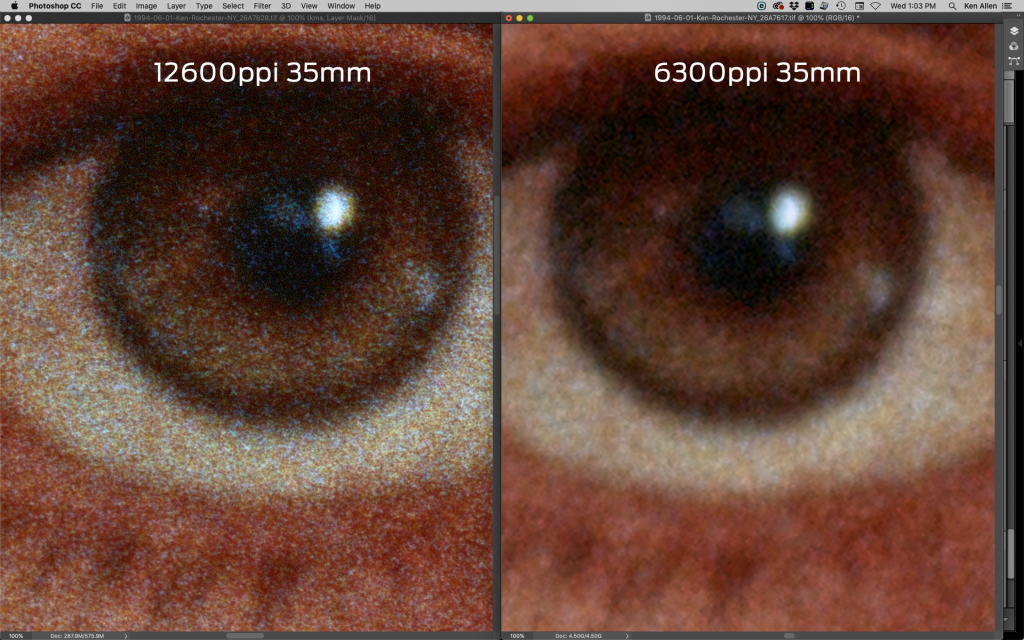

How do you know when you’ve captured all of the detail in your film? Look closely at the two eyeball close-ups (right image), In the eye on the left you can see clouds of cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes. When you see that, you’re imaging the underlying structure and are certain to have captured all of the detail. Do you need that much resolution, most likely not. Just setting the scale.

What are the other options?

“Drum scanning is the best!” In some cases, yes. The drum scanner can indeed deliver amazing quality. They have the three critical components:

- Super sharp APO macro optics

- Full spectrum pinpoint light source that limits flare.

- Analogue sensor (PMT Photomultiplier Tube) providing high dynamic range output.

BUT, let’s add up the downsides. A drum scanner has many physical and setting variables that are critical for a good quality scan. If the operator is not trained well or is not experienced the scan can have a myriad of scan problems that are not always evident unless compared to a good scan. Also, since they have not made a new drum scanner in over a decade it’s getting harder and harder to find an operational one. Making a good drum scan laborious, time-consuming, and hence expensive! A big issue is that some providers offer “Drum Scans” but are using flatbed scanners, so you’re not even getting the real thing if it is actually what you need. Lastly, depending on the film original many times other scanning methods can provide all the qualities you need at potentially much lower cost.

The one case in the last many years where I felt the need for a drum scan is when a client had a set of 8×10″ Ektachome and Kodachrome originals from the 1950’s. We were going to print large-format fine art prints for a museum collection. Everything had to be 100% perfect. The film needed to be scanned in extremely high detail, and we needed the dynamic range to see into the shadows.

What about the Imacon? This is also an excellent scanner especially for 35mm. Considering 6cm films and 4″x5″ films it’s sensor falls a little short. It is certainly good enough for 90% of the scanning applications, but if you are doing large format fine art prints, you are leaving some detail in the film and it is not making it to the print. Finally there remains the same issue of Time and Cost!

Conversely if you have a 35mm film, especially B&W film, the extra cost buys you nothing. The common desktop Nikon scanner does an ok job on B&W film. It’s a pretty sharp little scanner, although when you look at color, especially color positives, the Nikon scanners are stuck in a previous decade with it’s color and dynamic range severely lacking.

There is no cheaper way or slower to scan film than using a flatbed scanner. If you are just building an online family archive and have some time, this is probably the way to go. Many Pro/Am large format photographers get good results because the original is large which helps the optical resolution issue, but this is a limited approach when considering color positives. The flatbed scanners do not have the dynamic range of modern high-end sensors.

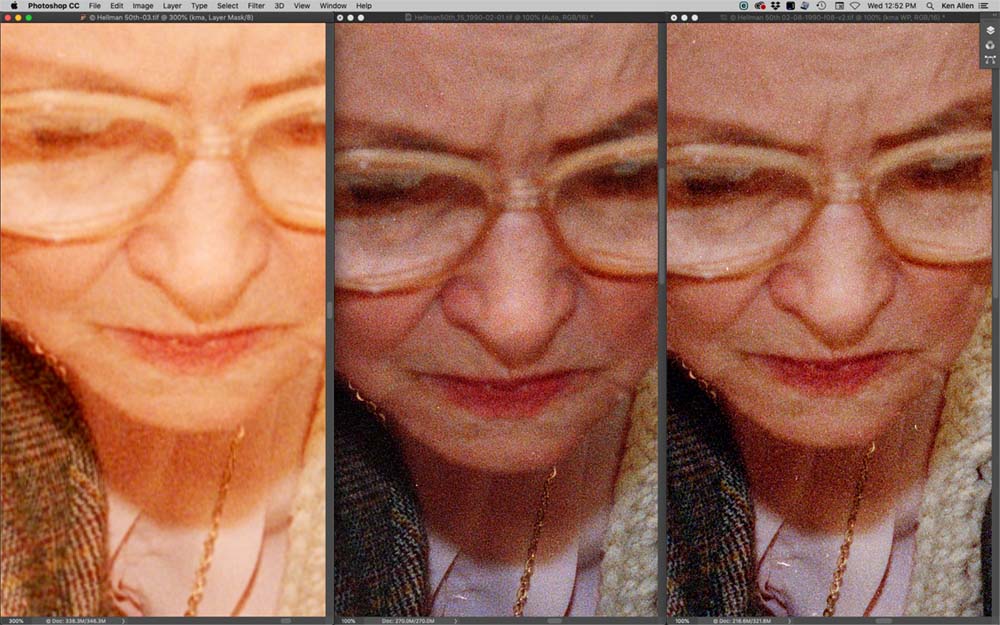

You can make a few conclusions from the three comparison images above. The Epson Flatbed scanning is not adequate good quality enlargement from small format film. The scan from the 50MP DSLR and the Imacon are essentially identical, any observable differences are only processing related.